The standard engineering story goes like this – someone thinks of a good idea, they found a startup to develop it, it gets backed by venture capitalists, it becomes a hit, everyone gets rich, and the field moves forward.

Boy that doesn’t happen often! I recently came across a much more typical journey. It was a lot more tortuous, and it took a really long time, but it does have a happy ending. It’s the path of low-power mesh networking from concept to craze to finally useful product. I heard one of the principals in this whole project, Lance Doherty, speak about his almost 30-year journey to actually make this work.

So here’s how this story went:

1997, Proposal. Prof Kristofer Pister of UC Berkeley cones up with a cool idea – Smart Dust. He could see that chips were getting steadily smaller and cheaper, and foresaw a day when they could be scattered around like grains of rice. Each would have a sensor and a tiny radio with just enough power to send a signal to another dust mote nearby. That could pass it on to another mote and another until it reached some useful destination.

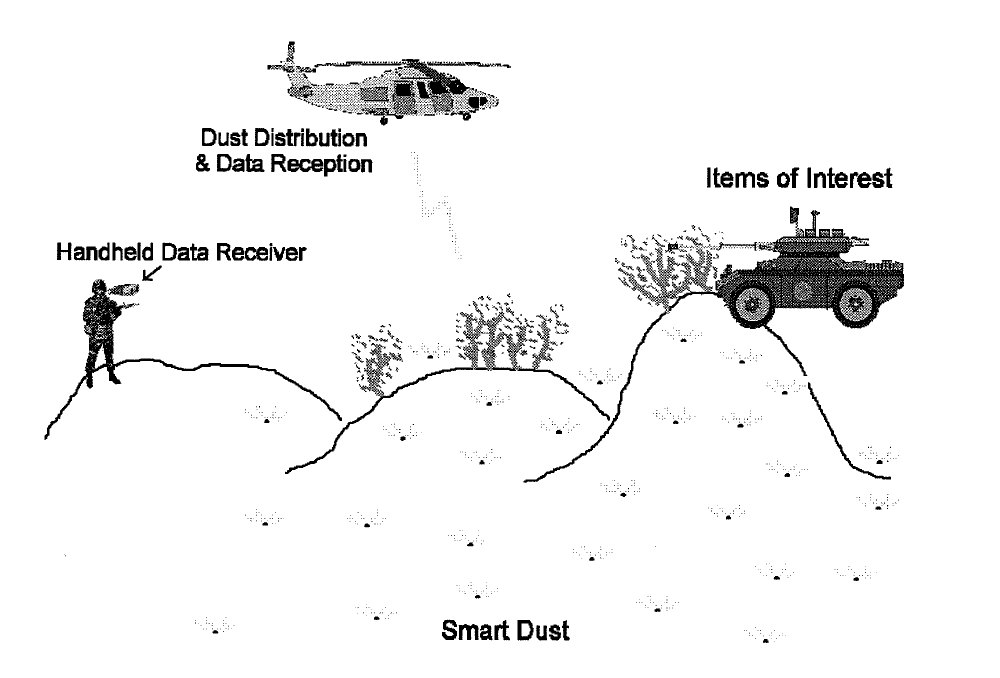

He gets funding from DARPA, the research arm of the Pentagon. For obscure historical reasons they’re the only federal agency that funds research into chips and computers. They have a creepy purpose in mind – they want to track every soldier and vehicle on a battlefield, the better to kill them.

2001, Demo – With the help of ace grad students like Doherty, they get a system working. It uses commercial parts and so is about 1″ on a side, but it can be deployed by a drone and dropped on the sides of roads to watch for vehicles:

It has a magnetometer that can detect the steel in a vehicle by the way it changes the Earth’s magnetic field, and can pick up cars 5 m away and trucks at 10 m

2004, Startup – They spin it out into a startup, Dust Networks, with venture capitalist money. Joy Weiss comes in as CEO. They figure out the key to the whole concept – each node must be time-synchronized to all the others so that it only has to turn on its power-hungry radio receiver when another node is likely to be transmitting. Leaving the receiver on all the time will kill whatever power is available.

They ride a rising wave of a new Valley fad, the Internet of Things. Just as they did with computer networking and later autonomous driving, the Valley follows DARPA’s lead. They think that the Internet will now be absolutely everywhere. They start adding processors and WiFi to refrigerators and washers and stoves. The high point is when Google acquires Nest Labs and their smart thermostat in 2011 for $3.2 billion. They envision acquiring data about absolutely everything in people’s homes and lives, the better to sell to advertisers.

That fails. The thermostat market is tiny and easily served by much cheaper widgets. No one wants talking refrigerators that creepily track your grocery consumption. No one trusts Alexa voice recognition boxes in every room, and rightly so.

Dust Networks also goes down around this time. They had some success in wireless networks in factories, with an installed base of maybe 20,000 places, but that’s not actually all that many for a chip company.

2011, Acquisition. They get bought by a strong Valley analog chip company called Linear Technology. Linear had done extremely well by building radio chips, analog-to-digital converter chips and power management chips, ones that change one DC voltage efficiently into several others. These are needed everywhere. They explicitly avoid getting into price wars for commodity parts since that drops profits to zero. Instead they aim for steadily higher performance and better features, and that lets them do fun engineering.

They discover an ideal use for these low-power networks – electric vehicle battery packs. These contain dozens of battery cells and each one of them needs a control and monitor chip. The chips can tell how much charge a battery holds, what temperature it’s at, and most crucially, whether it’s going to catch fire. Lithium battery fires are horrible. They’re very hard to extinguish and emit toxic smoke. If the battery is mis-charged, it can heat itself up so much that it goes into thermal runaway, and you have very unhappy car owners, assuming they live.

Running wires to all these control chips is a nightmare for the wiring harness, for labor, and for reliability. So what if they could all be connected by radio instead?

You don’t need to send a lot of data back and forth, just enough to know what each battery is doing. The connection has to be extremely reliable, and the power draw has to be minimized since it’s running on the battery itself. Yet this lets you connect the chip to the cell when it’s first made and then follow it for its entire life. You can tell what happens to it in the factory, in the truck that delivers it, when it’s installed in a car, during the car’s lifetime, and then in whatever other use the battery is put to after the car is done. You can know the cell’s capacity exactly instead of having to build some margin in in case of mis-measurement. That alone lets you get another few percent out of each cell. Plus you save the weight of the wiring, and can reconfigure the packs easily for different models.

By 2016 they have installed these wireless Battery Management Systems (wBMS) in an electric BMW i3 and driven it all over the place. It works great! They show it at the 2016 Electronica conference and it’s a smash. They think “Ah, it’s working at last.”

2017, Productization – That’s when reality kicks in. Proving that the radio data will get through in every possible circumstance is really hard, but car companies won’t accept it without thorough testing. Linear doesn’t have the resources to do it. Yet their Massachusetts competitor Analog Devices does. They buy Linear in 2017 for $14.5 billion with about 25% in stock and the rest in cash.

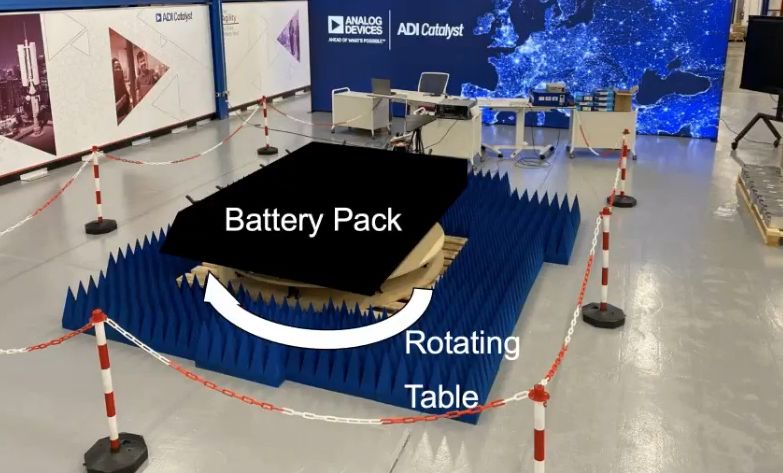

They set up a testing facility at the ADI plant in Limerick, Ireland. It’s got a turntable that can hold a whole battery pack and orient it every which way. They surround it with radio antennas so they can blast it with every kind of interference.

It takes years to work out all the possible failure modes and needs engineering groups from all over the world. Yet then GM agrees to use it! They had some bad fires with the first Bolt model and were being extra careful for the next ones. They initially called it the Ultium battery system, but that was too hard to explain and they’ve dropped it. GM starts shipping it in 2021.

At the same time they’re approaching all the other car companies. Now that one major company has accepted it, it should be fine for everyone, right? Ha. This company wants the controllers to be on all the time in case the batteries overheat in a sunny parking lot. Yet it all has to work on the 12V lead-acid battery, since everything else in the car is designed around that. If it sits there for a month, the idle power will kill the 12V battery, so nuh-uh. That can be fixed in software, thankfully. This other company wants to get a lot more bandwidth out of each controller to monitor it more closely. Yet another wants the maximum level of safety for all the chips and the design process that goes into them.

Every new user has new demands. It’s wasn’t until they got to the seventh customer that they could actually use the system as is. That didn’t happen until this year. There are bound to be further glitches as the scheme spreads, but they’re finally off and running.

So from initial concept in 1997 to shipping in 2021 is 24 years. That’s a good chunk of a career! It’s been a long road. Yet it’s saving lives and easing the electrification of cars, and ultimately helping the planet. It didn’t work to find soldier’s footsteps (it’s not used in Ukraine even now), and it didn’t work to network toasters because no one cared, but it finally found a place where it’s really useful. Let’s hope they now find some more!

Interesting!