WGBH, the main Boston public radio station, has just done a great series on The Big Dig. You can find the podcast here: The Big Dig, and the start of the series on Youtube here: The Big Dig began with activists who hated highways. It’s written and narrated by Ian Coss, and goes over the full history of the massive project. His main interest in what it says about how we’ll deal with even bigger projects in the future, like protecting cities from sea level rise. It was vastly expensive, about $16B, but saved Boston in a direct way. The entire story is fascinating, but let me concentrate on one part of it, the brilliant innovations that made the whole thing possible. There’s a lot to cover, so let me do this in more than one part. Let’s start with the key concept:

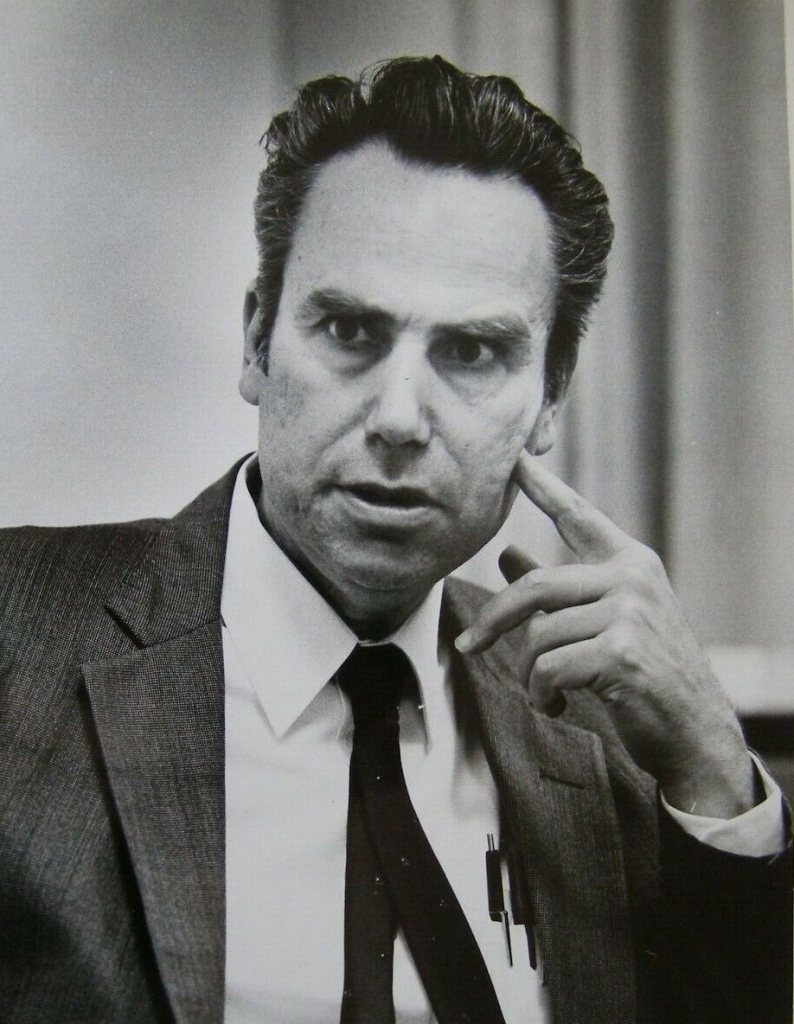

Combining the Artery and Harbor Tunnels – The entire Big Dig project was driven by one Fred Salvucci, a Boston-born MIT-trained civil engineer who was an anti-highway activist in the 1960s. His own grandmother’s house had been taken by one of the projects, leaving her with nothing. In the early 70s he was in charge of transportation for the city of Boston under Mayor Kevin White. He was at all the meetings arguing about what should be built, and his opponent was often a road guy named Bill Reynolds. In spite of their differences, they would go drinking together at Jacob Wirth’s, a downtown dive with sawdust on the floor. It’s now gone, displaced by the glossier Boston that the Dig helped create. As Salvucci recalls, Reynolds said to him:

“You know, I’ve been trying to figure out why you guys don’t like highways, cuz highways are beautiful things. They’ve built America, they’ve built a middle class. And I’ve come to the conclusion that the reason you don’t like highways is because the elevated Central Artery is such a big, ugly, dysfunctional thing. It’s like a giant neon sign flashing saying: highways are bad, highways are ugly, highways don’t work. So I’ve come to the conclusion that to get the root of the problem, we have to tear down the Central Artery and rebuild it underground.”

Salvucci replied “Gee Bill, that’s a wonderful image, but we’re gonna have to put a sign up at the Charles River: city closed for alterations, come back in 10 years. How the hell are we gonna do this thing without shutting the city down?”

Reynolds told him to just solve it, and that’s just what he did. Salvucci would walk under the Artery from City Hall for lunch, and the plan formed. There was nothing underneath the Artery. If the elevated highway supports could be held up by putting beams beneath them, the whole tunnel could be dug beneath it.

Yet that wasn’t enough. There was a competing massive infrastructure project, one to build a third tunnel under Boston harbor to connect the city with its airport. Business people desperately wanted the Tunnel because the existing tunnels were small and jammed. I remember one time when a truck lost its brakes in one of the tunnels and jammed itself between the roof and a BMW. That shut down the city for a day.

Transit people didn’t care about the Tunnel because there was already a good subway line to the airport, and they hated the Artery more. Worse, building a new Tunnel would destroy the neighborhoods of East Boston when it emerged from under the water. Tip O’Neill, the great congressman from North Cambridge and then Speaker of the House, would never agree to anything that harmed his constituents.

That’s when Reynolds re-appeared in the story. He called Salvucci from a pay phone by South Station and told him “You have to come down here.” They met and Reynolds showed him a Tunnel route that would come up on the airport itself, and not take a single East Boston property. It would be longer, and have to go under the South Station railroad tracks and under a waterway called Fort Point Channel, but it could be done.

The only way to resolve the conflict between the opponents of the Artery and the proponents of the Tunnel was to do both. It would cost an enormous amount, but Tip O’Neill would handle that part. They eventually named the new Artery for him!

Here’s what the Central Artery and Tunnel (CAT) Project (its official name) ended up being:

The buried Artery goes just about where the elevated Artery used to run, right through the heart of downtown, and the Tunnel swings way around to avoid Eastie.

This was all non-obvious. Depress this enormous highway while keeping it open? Double the cost by building a harbor tunnel too? Madness! Yet both had to be done, and the only way to get enough support was to do them both. Fortunately, Mike Dukakis was elected governor in 1974, and be brought in Salvucci as head of the Dept of Transportation. There he was, only 34, and about to start the most momentous reworking of this ancient city that it had ever seen. Yet how could it be done? That’s for next time.