And now for something completely different! Jack Ryan did not create fundamental innovations like Federico Faggin and the self-aligned FET, or Robert Dennard and the DRAM. He did not have a long, successful career with a strong and supportive family. He did get involved in massive lawsuits. He did throw infamous Hollywood parties full of drugs and starlets. He did come to a bad end. Yet he also created things that have brought more direct pleasure to more people than either of my previous Obscure Creators. He’s the inventor of the Mattel toys Barbie, Chatty Cathy and Hot Wheels!

Not that Mattel will admit that, but more on that later.

He was born in 1926 to a well-to-do family in New York. His father was a builder, and he was a tinkerer all through his teens. He graduated from Yale in 1948 with a degree in electrical engineering, and then moved to the Boston area to work at Raytheon. They were just starting up with radar-guided missiles, and he worked on the Sparrow III air-to-air missile and the Hawk surface-to-air. These are still in use after many upgrades. Yet Cold War work was depressing, as was gray New England. He was sent on business trips to sunny, relaxed southern California and loved it. In 1955 he quit Raytheon and moved his whole family there.

He had already met Ruth and Elliot Handler, the founders of Mattel. They had just had their first success, a toy called the Burp Gun, which they promoted through an exclusive and expensive deal on the Disney Mickey Mouse Club TV show. They pioneered TV sponsorship, but it took all their cash. It was a big risk, but they sold a million of them in the first year. Ryan wanted to work with them, but knew they had no money. Instead, he negotiated a deal where he got 1.5% of the gross on all the toys he designed for them. They were delighted – they got this obviously talented guy for free.

Both Ryan and Ruth Handler first wanted to do a better doll. He had seen how girls played with paper dolls instead of the expensive ones on their shelves because “they had dopey figures.” Ruth had just been on a vacation in Germany, and saw just what she was after, a curvy doll called Bild-Lili. It was based on a racy cartoon, Lili, in the German magazine Bild. She brought one back and that became their model:

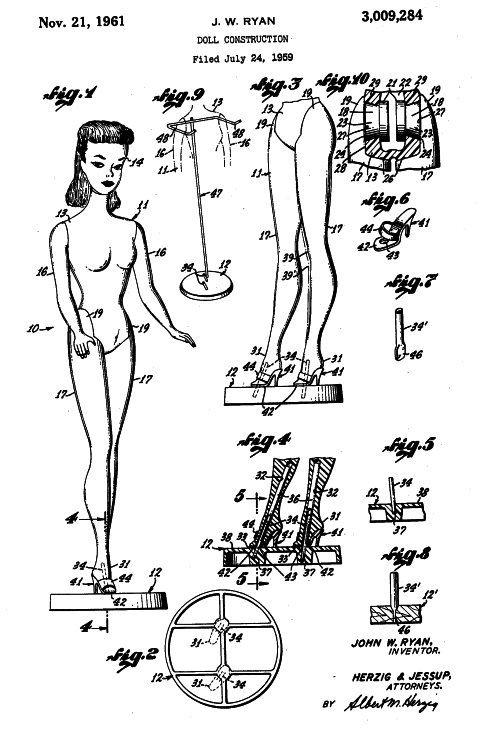

Different eyebrows, but same figure. Ryan designed the mold and the internal armature. He even got a patent for it!

He received about 215 patents all told between 1959 and 1980, with most going to Mattel, some to him personally like the above, and others to the Ideal Toy Corporation. Almost all were for toys, but he also devised a coffee cup that would keep beverages at a constant temperature (probably using a phase change of sodium acetate), and a camera that could develop its own film.

Barbie was a huge success right away, and is to the present day. Part of that is her shape, part is her articulation (which was much more natural than other dolls), and part her houses, all of which Ryan designed. I don’t think he did her clothes, but that’s a big part of the appeal too.

However, Ruth Handler claimed complete credit for Barbie in her 1994 memoir “Dream Doll”. She said that the doll was named after her daughter Barbara, but Ryan’s wife was a Barbara too, and she looked a lot more like this. The portrait of Handler in the recent “Barbie” movie is complete corporate spin – she was a tough-as-nails business-woman and somewhat crooked, and not at all the lovable nana seen there. Handler’s own taste was prim and conservative, while Ryan’s was completely wild, so he was far more likely to devise a sexy toy. That said, he did chicken out just before the doll went into production, and filed the nipples off of the mold.

He soon followed that up with Chatty Cathy, a doll that could speak up to 11 phrases. It was not electronic – it had a tiny phonograph record holding the sound. The pull string would wind a coil, and a needle would drop onto the record. It was attached to a paper cone for amplification, just like the great horns of the original phonographs. It’s a brilliant design and was used by all talking toys up until it could be done even more cheaply by chips in the 1980s.

Even though he was never an employee of Mattel, he was their head of R&D. Not only did he do the mechanical design of the toys, he studied how children interacted with them. That’s because he was a real engineer, not just a tinkerer, and that means being systematic. He set up play areas with prototypes and had psychologists evaluate them. This became another reason for Mattel’s success.

His biggest hit after Barbie was Hot Wheels. Elliot Handler had looked with envy at the success of the English Matchbox cars. He wanted to do the same but using snazzier SoCal hot rod designs. Harry Bradley was hired out of Chevrolet to design the shells and paint jobs, while Ryan did the mechanicals.

Bradley had caught polio at age 14, which paralyzed him from the waist down. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he spent his whole career designing ultra-cool ways to get around, including the Oscar Meyer Wienermobile and the Dodge Deora.

Unlike Matchbox, Ryan put plastic wheels on the cars with a little give for traction, needle bearings for smooth motion, and a suspension. He also came out with the orange track system that let kids build raceways, and they even had a battery-powered accelerator that would shove the cars along. The result was that the cars totally zoomed. This too was an instant hit, and is still everywhere. Like his wife, Elliot Handler later claimed credit for them, and relegated Ryan to the role of technician.

Mattel sold six billion Hot Wheels cars in their first 50 years, from 1968 to 2018. When my son was small he had dozens of them, and he gave them all personalities. He would line them up on the edge of the bathtub and tell stories about them. Maybe that wasn’t so different from Barbie after all.

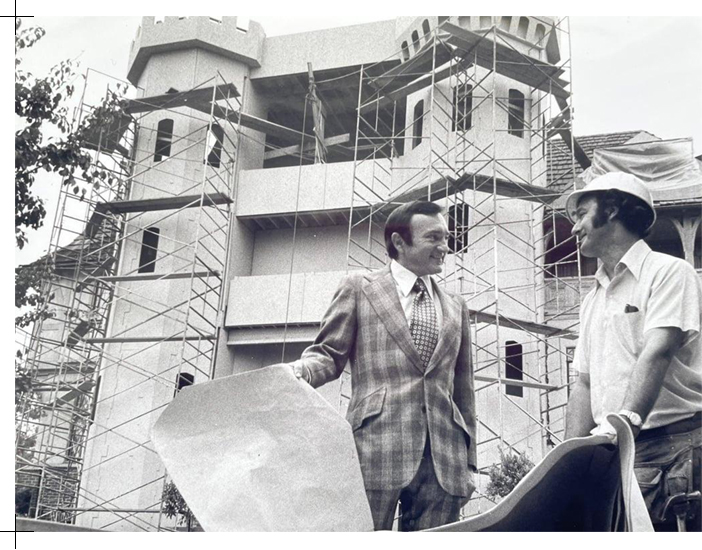

So in the 1960s, Ryan was making a 1.5% royalty on toys that was selling for hundreds of millions. A million bucks a year barely gets you into the 1% these days, but was serious money back then. It all went to his head. He bought an enormous mansion in Bel Air which he called The Castle:

He hired Hollywood set designers to rebuild it as a literal castle, but with plywood and sheetrock. He never actually finished it because that would be no fun. The first floor became an enormous banquet room paneled in black fur. He would hold Tom Jones feasts there, where everything had to be eaten with your hands, and you couldn’t even use napkins – you had to lick your neighbor’s fingers clean.

The master bedroom had mirrors everywhere. One time he was lying in bed there with Gwen Florea, the tall, voluptuous redhead who was the voice of the first talking Barbie. She later related that he had said “You know something kid? I should cut a hole in the ceiling so that when I make love I can look up and see the sun and the moon. Wouldn’t that be just delightful?” Yes, the Sixties.

You can hear a lot more about this in Jerry Oppenheimer’s savage take on the rise of Mattel, “Toy Monster” (2009), and in his daughter’s Ann’s accounts in Dream House – the Real Story of Jack Ryan. Ann and his other daughter Diane remember him with great fondness, but they saw a lot less of him after their mother gave up on him in 1971. His strict Catholic father had died by then, and they were finally free to divorce.

Other things started going wrong in the 70s. The Handlers disapproved of his lifestyle, thinking it damaged the brand, and resented the royalties. They set up an alternate R&D division to take work away from him, and hired a demanding ex-military guy to run it. It was a disaster for both sides. The company started losing money, and the Handlers hid the losses using various financial tricks. The SEC found out about it, and they were forced to resign from the company in 1975.

They first stiffed Ryan on his royalties. He sued them for $24 million, and they simply stalled. He had burned up most of his money by then, and the legal bills were huge. He had to sell the Castle for a pittance. He went through several more wives, including Gabor. He was owed money on about 200 products he had done for them, and they had him under deposition for 200 days over three years. They finally settled in 1980 for $10 million, but only after he had had a heart attack and needed a quintuple bypass.

He was still inventing in the 1980s, and had settled down somewhat, when the final blow came. He had a stroke in 1989 that robbed him of speech and left him paralyzed down his right side. All he could do was lie in bed and watch TV. His last wife, Magda, found him on the floor of their bedroom in 1991 with a gun in his hand. He had written “I love you” on their mirror and then pulled the trigger. He was 64.

Did the libertine lifestyle of LA do him in? Maybe, but probably not. He had always been manic-depressive, and rather sex-crazed. Even if he had stayed in the staid Northeast, he would have had mistresses on the side. He would probably have drunk himself to death, as so many of his class do, and that’s just as hard an end as cocaine.

What LA did permit was to let his imagination run wild. With that much money he could do anything he wanted, and people would be amused instead of appalled. A lot of what he did was frivolous, and some was self-destructive, but Mattel, and kids everywhere, benefited when his ideas became concrete.

Excellent! What an interesting story

Pingback: Execs Erasing Techs | A Niche in the Library of Babel