My wife and I recently went to the Shaw Festival at Niagara-on-the-Lake Ontario. This has been presenting plays by George Barnard Shaw and other 20th century playwrights every summer for the last 60 years. It’s held in a perfect little town full of flower baskets. The whole area is the Riviera of eastern Canada, with mild winters, orchards and wineries everywhere, and lots of views over the grand Niagara River.

Yet maybe you’re not all in on witty old comedies and quaint shops. Maybe you’re into Big Iron, or at least your wife thinks so. She found the awesome Niagara Parks Power Station just a few miles up the River:

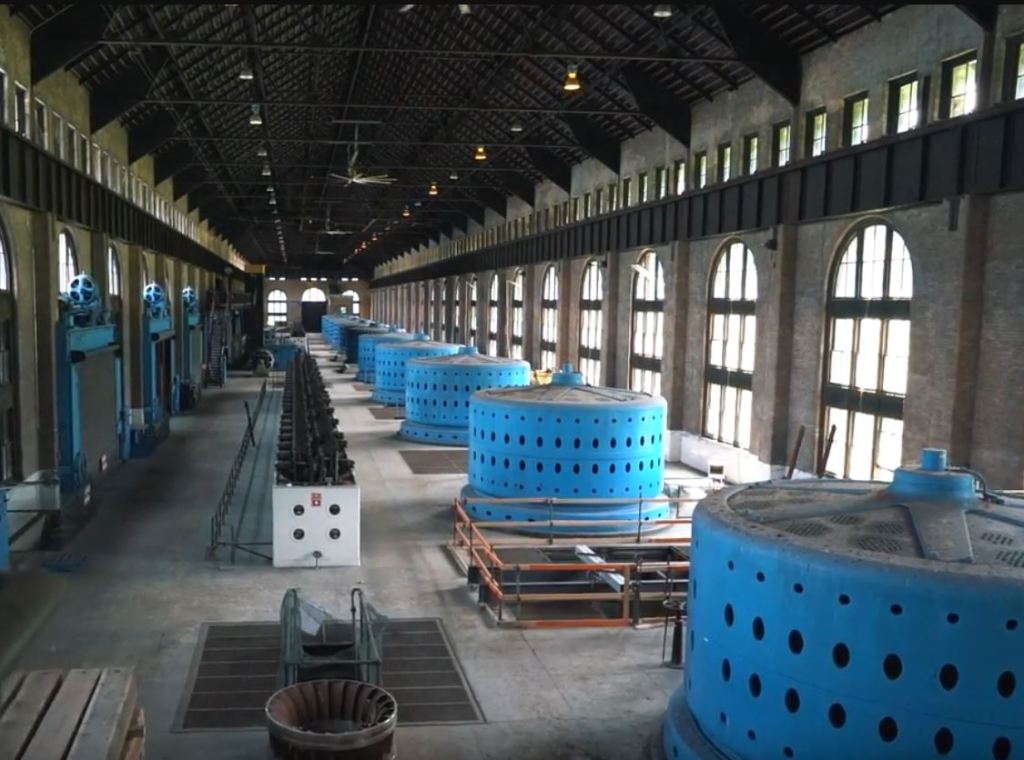

Its main hall here is a thousand feet long and a hundred high. It contains 11 of those huge blue alternators 1 . Each one sits on top of a shaft that drops 130 feet down to a water turbine at the bottom. It’s located right beside the top of the Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side, and diverted water from it. It was one of the first power stations built to harness the Falls in 1905, and it ran until 2006 (!).

Once the water falls down the shafts and through the turbines, it flows down an enormous outfall tunnel out to the base of the Falls. You can now take an elevator down to the tunnel and walk out:

It’s about a half mile long and 40 feet high. It needed that enormous volume to hold the flow of water coming out. At the end you see:

That’s a hundred thousand cubic feet of water a second falling down in front of you. You can just make out a tourist boat going around the base. The American ones had everyone in blue ponchos while the Canadian ones were all red.

How is it that a huge installation like this could operate for over a century? One reason has to be that it produced dead cheap power. Once something like this is built it runs on its own. The main maintenance is to keep stuff in the water from damaging the turbines, so someone has to keep all the logs and branches and canoeists having a really bad day from actually going into the flumes. Otherwise the water flows in, the turbines go round, the alternator magnets spin, and the power goes off into Ontario.

Yet there’s another, odder reason. The entire power grid of North America has been set to run at 60 Hz for the last hundred years. That number was picked somewhat randomly early in the 20th century. It’s high enough that the flicker in incandescent light bulbs isn’t visible to the human eye, but otherwise there’s no special reason for it. Europe randomly picked 50 Hz, maybe to give local electrical manufacturers an edge over American ones.

This plant generated 25 Hz. It predated the standardization on 60 Hz. It could not be connected to the grid! It had to go to specific users, ones that could handle the weird frequency. There appear to have been two main kinds of customers – electric trains and aluminum smelters. The street cars of Toronto could use the 25 Hz directly in their motors. It was much more efficient than 60 Hz because of losses in the iron poles of their electromagnets whenever the magnetic direction switched. Amtrak uses 25 Hz to this day in lines in New York and Pennsylvania and has its own hydropower stations to generate it. Aluminum smelters need DC, and lots of it, and it’s easier to convert from 25 Hz to DC than it is from 60 Hz. Most of the cost of aluminum is in the electricity used to smelt it, so this really mattered to them.

All of their customers loved the low cost power, but ended up locked into them because of the non-standard frequency. That really lengthened the plant’s lifetime! But by the early 2000s everyone had to bow to using standards. In the latter part of its operation, the main income was selling the water flow rights to other, more modern plants down stream. The main one is the Adam Beck Station. It’s fed by a canal from the top of the Falls and is far larger: 2000 MW vs the 80 MW here.

So it had to be closed eventually. It ran for so long that seismic shifts in the bedrock were throwing the turbines and alternators out of alignment. They converted it into this museum and re-opened it in 2021.

I should mention one other aspect of this that impressed this electrical engineer – this enormous plant contains no electronics at all. It predates even vacuum tubes! All the control of these enormous machines is done mechanically. The alternators all need to run in exact sync at exactly 250 rpm, and that was done with ball governors much like Watt’s steam engines of a hundred years earlier. There were huge banks of switches next to them that were immersed in oil to keep from arcing, and variable resistors the size of cars to control the voltage. We can put tens of billions of transistors on a chip these days, and this whole plant wouldn’t have used one.

Anyway, the old line is that real engineering is where if you fall off of it, you die. Here’s one piece of engineering that qualifies!

- In alternators the power coils are stationary while the magnets turn, while in generators it’s the reverse. The electromagnets can be inside the power coils, like here, or outside fixed coils. Fixed power coils let alternators have fixed power wires while generators have to take the power off of slip rings on the moving power coils. This gives alternators a big advantage for high-power systems like this, since the brushes on the slip rings spark and wear out, but it does mean that they can only produce alternating current (AC). Generators can produce AC or DC depending on how the slip rings are connected. Electromagnets inside the alternator still need power as well, but far less, so they’re fed from slip rings. The alternators start from big battery banks and can then power their own electromagnets. ↩︎

Yes, indeed – and the Tesla Coils that you can play with and hear are very cool, too. FYI for interested potential tourists!