The physicists used to have all the fun, what with building species-ending weapons and ominously declaring that I Am Become Death. Yet nukes turned out to be useless for actual military purposes, as Putin has discovered to his dismay, and nuclear power is moribund.

So now it’s the chemists’ turn! Climate change is largely a problem of chemistry, of the infrared absorption of CO2 and CH4 to be exact, and now they get to step up to the plate. Money is being thrown at them to develop batteries that are denser or safer or longer-lasting or cheaper, and to remove emissions from every manufacturing process.

I saw this quite directly at the MIT 2024 Technology Day on June 1st. Every year they invite alumni to listen to various professors talk on a common topic, and this year that was climate change. Apparently some 20% of the faculty are working on it in some way. MIT’s official charter from the State of Massachusetts in 1861 is to do exactly things like this:

….Are hereby made a body corporate by the name of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for the purpose of instituting and maintaining a society of arts, a museum of arts, and a school of industrial science, and aiding generally, by suitable means, the advancement, development and practical application of science in connection with arts, agriculture, manufactures, and commerce.

So that’s no surprise. The whole program can be found here, of which this is the first part:

Watching video is slow, though, so let me summarize a few of the talks:

Yellow Hot Graphite Thermal Batteries – Prof Asegun Henry, Mechanical Engineering, founder of Fourth Power

Batteries need to be an order of magnitude cheaper per kilowatt-hour, and we’re not going to get that through lithium-ion. Instead let’s store the energy as heat in something cheap, like blocks of pure carbon. The energy density goes up as the fourth power of temperature, so it needs to run as hot as possible. This is what distinguishes this work from other efforts like Antora Energy – they run at 2400 C while Antora is at 1500 C. Instead of using simple resistive heating, FP uses ceramic pipes full of molten tin, moved by pumps with graphite components. Electricity is drawn out through thermo-photo-voltaic panels, which are solar cells that are tuned for infrared and can have efficiencies as high as 50%. The rest of the energy is used as process heat in industries. The blocks are kept in sealed, insulated shipping containers filled with argon so they don’t catch fire. They’re aiming for $25/MWh, 10X less than Li-ion. They’ve got a great name for it – “Sun In a Box”.

Breaking Down Methane – Prof Desirée Plata, Civil and Environmental Engineering, founder of Moxair

Methane is a far worse greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and its level is rising too from industrial emissions. Even though its concentration is > 200X less than CO2, it accounts for about 30% of global warming so far. The biggest emissions are from leaks from natural gas distribution, but those are too diffuse to do much about. The best opportunity to reduce it is at point sources. There are two big ones there: dairy barns and coal mines. These both have powerful ventilation systems to maintain air quality, so those vents a great place to break down methane. Moxair has found a catalyst that combines methane and oxygen, and put it into clay pellets like cat litter that can be used as a filter in the ventilation. The reaction runs hot, but it’s being blown outside anyway.

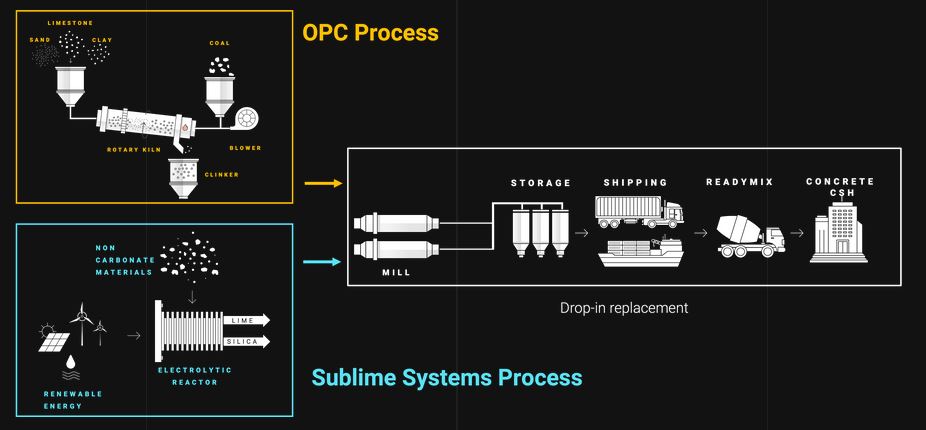

Green Cement – Prof Yet-Ming Chiang, Dept of Materials Science, founder of Sublime Systems

Concrete is far and away the most common construction material, and making the Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) that holds it together accounts for >7% of worldwide CO2 emissions. These come from two sources: the heat used in the cement kilns, and the CO2 from the limestone itself as it is cooked with sand and water into OPC. The final product is various combinations of calcium, oxygen, silicon, aluminum, and iron. Prof Chiang starts with a non-carbonate mineral (which they don’t mention), grinds it up, and extracts the calcium via electrolysis. It ends up being just as strong and tough as OPC, and compatible with concrete mixing and handling.

They have a 250 ton/year plant in Somerville MA now, and will have a 1000 ton/year plant out in Holyoke MA in 2026. Holyoke has a large dam on the Connecticut River for supplying clean power. The Mass Green High Performance Computing Center is sited there for the same reason.

However, the US produces 90 Mtonnes of OPC a year and China produces far more, so this has to scale by five to six orders of magnitude. Cement is such an enormous business that the recent crash in Chinese construction caused a visible decrease in worldwide emissions all by itself.

Sure hope this matters!

All of these ideas are still at the laboratory stage. That’s OK – it’s what MIT is for, and tech has to start somewhere. Yet it’ll take decades for them to make a difference. It’s too bad that this work didn’t start in 1997 after the Kyoto Protocol made it an international issue, but here we are. The warming used to be slow but is now quicker every year. We’re now getting to the steep part of the S curve. It’s like the famous Hemingway quote from “The Sun Also Rises”:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

The bill for fossil fuel usage is now coming due! These ideas are now not just interesting experiments but crucial.

Pingback: MIT Under Attack | A Niche in the Library of Babel